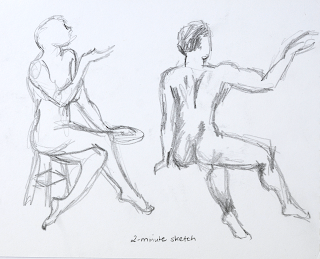

To initiate this exercise I watched a tutorial Drawing the Figure in Motion with Robert Liberace, 2009. What I found interesting was how Liberace's knowledge of muscular form helped to inform his drawing. In places he over-emphasized the form of various muscle groups to ensure that his drawing showed the dynamics of the movement. It wasn't specifically related to faces, but as I worked I tried to seek out the muscles of the face to interpret the shape of the forms and shadows.

As I keep seeking for a more gestural, expressive style, I read up about Gestural Tone in Drawing Projects. The description drew attention to "exotropic tone", tone outside the figure/object, and "endotropic tone", tone found inside the figure/form. (p. 168 Mick Maslen and Jack Southern, 2014.) In the exercise it talks about discovering the edges of boundaries of objects by putting tones in the shape of those tonal areas working the negative space simultaneously from large shapes to smaller shapes.

I started exploring features by drawing the eye of a young woman, the eyes of a 6-month-old baby, and a young man. In each of these drawings I started with a 2B pencil seeking to rely less on contour lines and more on planes of tones, hatched in with directional strokes. I then strengthened the darker areas with a 6B pencil. I found the main difference between drawing the eyes of the child and those of the young man was the fact that the space between the eyes of a baby is shallow and less defined by shadows, whereas the adult's nose forms a very sharp ridge of shadows where the bridge of the nose forms between the eyes. The shadows around the eyes are also less pronounced. The circular shape of the eyeball of the man is very evident in the circular shape of the shadow beneath his eye.

As I keep seeking for a more gestural, expressive style, I read up about Gestural Tone in Drawing Projects. The description drew attention to "exotropic tone", tone outside the figure/object, and "endotropic tone", tone found inside the figure/form. (p. 168 Mick Maslen and Jack Southern, 2014.) In the exercise it talks about discovering the edges of boundaries of objects by putting tones in the shape of those tonal areas working the negative space simultaneously from large shapes to smaller shapes.

I started exploring features by drawing the eye of a young woman, the eyes of a 6-month-old baby, and a young man. In each of these drawings I started with a 2B pencil seeking to rely less on contour lines and more on planes of tones, hatched in with directional strokes. I then strengthened the darker areas with a 6B pencil. I found the main difference between drawing the eyes of the child and those of the young man was the fact that the space between the eyes of a baby is shallow and less defined by shadows, whereas the adult's nose forms a very sharp ridge of shadows where the bridge of the nose forms between the eyes. The shadows around the eyes are also less pronounced. The circular shape of the eyeball of the man is very evident in the circular shape of the shadow beneath his eye.

|

| Fig. 1 Eyes Studies |

I then decided to see how different the features of a young Kazakh boy would be by comparison. On the same page in my sketchbook I explored the features of a boy I have photographed. Once again I tried to explore planes of tones and keep a loose style. I sought out the endotropic and expotropic forms as I modelled his face.

The house where I am working has a National Geographic magazine, Tomb Raiders with a young Matsigenka girl, Yoina Mameria Nontsotega, photographed in it (James, June 2016). As we visited a number of Amazonian Indian tribes during our years in Venezuela, I was drawn to her photograph. I decided to sketch her in my sketchbook using watercolor crayons, watercolor black pencil, and washes of water. I enjoy the sketchy interpretation that resulted as there is limited control over this media, due to the thickness of the crayon and the fluidity of the washes. I would like to explore this medium more.

I started drawing her from the area of the nose and then worked outwards. My resulting image has over-emphasized her eyes - particularly the right one. Her nose is actually far more refined in the photograph. So there are things that would be tweaked if I were to develop this into a final work. What I might do is to use her as the basis of my portrait drawn from memory.

|

| Fig. 3 Whole head study |

Works Cited

James, C. H., June 2016. Photograph of Yoina Mameria Nontsotega. [Photograph] (National Geographic Magazine).

Mick Maslen and Jack Southern, 2014. Drawing Projects. London: Black Dog Publishing.